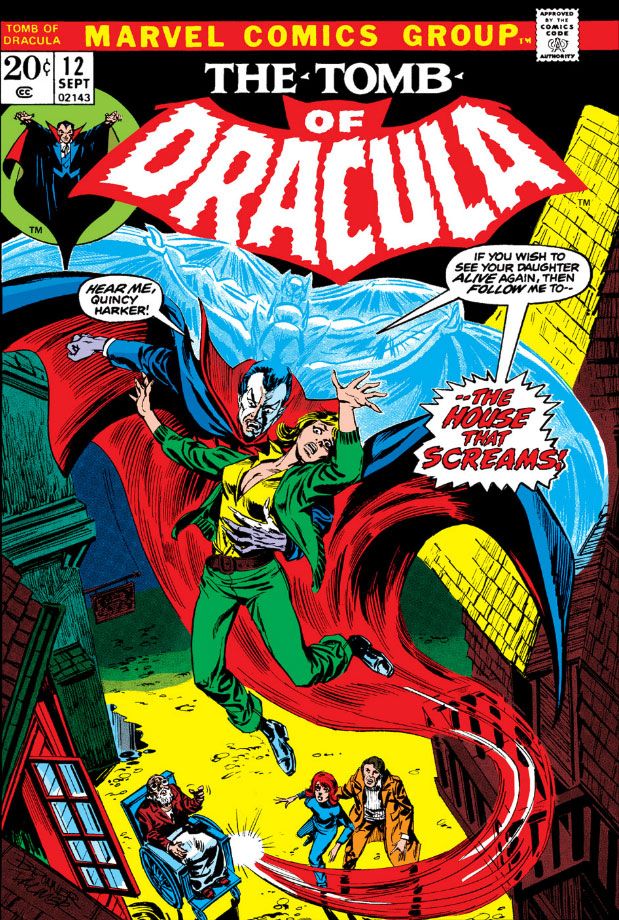

Is it controversial to say Tomb of Dracula was Marvel's best comic of the 1970s? It has some strong competition from Conan the Barbarian where Barry Windsor-Smith displayed exponential artistic growth; from X-Men/The Uncanny X-Men with Chris Claremont, Dave Cockrum and then John Byrne creating a mythos that won all those Eagle Awards and underpins the entire Marvel universe to this day; and from Howard the Duck where Steve Gerber and artists like Frank Brunner, Val Mayerik and Gene Colan inspired Marvel's first movie adaptation (an infamously lousy one, but still a big budget, George Lucas-produced film released to theaters in the belief it would be a big hit).

Those are all fine series, and I've enjoyed each of them. But Tomb is just something else entirely. Tomb is like wow times wowee for a little "wowee-wow-wow." Tomb took an exhausted public domain property-- good ol' Count Dracula, star of dozens of movies, TV shows and comic books in one form or another-- and gave it a compelling, new un-life. Writer Marv Wolfman's melodramatic prose perfectly matches Gene Colan's shadowy visuals, the two elements working in tandem like peanut butter and chocolate in a Reese's. When Marvel finally teamed Colan with inker Tom Palmer, the two produced what I will argue was consistently the most breathtakingly beautiful color monthly of the entire decade.

Operating on the fringes of the Marvel universe, Tomb functions as a sequel and expansion of Bram Stoker's novel. In fact, lead good guy Frank Drake is a descendant of Dracula himself, his last name an Americanized version of the original. Quincy Harker comes right out of the original book, the first born child of Jonathan and Mina (nee Murray) Harker, conceived and born after the novel's main events and named after one of Dracula's victims, the Harkers' courageous American cowboy friend Quincy Morris. Wolfman casts Harker in the Dr. Van Helsing role. More troubled than his Stokerian prototype, Harker rides around in a weaponized wheelchair the likes of which James Bond's pal Q would envy, and he uses it to save himself and others several times throughout the stories. His hardboiled protégé (and later, Drake's lover), Rachel van Helsing, is the grand-daughter of the Stoker character. Both Taj Nital, devoted companion to Rachel, and-- most significantly-- Blade, the ultra-cool, Blaxploitation-style member of the group, are wholly original. At least I don't remember Stoker having watched Shaft, Super Fly or Hammer, but he could very well have despite having died about 60 years before the birth of the film genre.

Every October, I turn to Tomb of Dracula and it helps put me in that spooky, haunted Halloween mood. It has its funky idiosyncrasies-- too many scenes where Rachel, Frank and Blade confront Dracula and all they do is trade arch insults and a whole lotta plots where Dracula almost dies, only to escape at the last moment. After all, how many times can our vamp-slaying crew almost destroy Dracula before they start to seem completely incompetent to the point they lose our sympathies and incur our scorn, like that bumbling Gilligan? Tomb of Dracula ends rather abruptly with issue #70 before it has a chance to devolve into self-parody, but even when things turn silly as they occasionally do, the overall atmosphere remains one of effectively updated gothic horror, and there are still plenty of genuinely creepy moments to restore our faith. Which finally brings us to tonight's topic, Tomb of Dracula #12 (September 1973) and a little story we like to call "Night of the Screaming House." Because that's what Marv Wolfman named it.

Oh, on the Frank Brunner-illustrated cover, Dracula calls it the "House that Screams," but you should never believe anything the king of the vampires tells you. He has his own agenda and will lie when it suits him.

Okay, forget Dracula before... er... remembering him again. Because Wolfman and Colan throw us right into the action with the main characters locked in a ferocious show-down with none other than Dracula, who has caught himself a delicious dinner, but can't catch a moment to eat in peace. It's not a holdover from a cliffhanger ending to the previous issue (in which Dracula fought some motorcycle guys who aren't quite as menacing as the Sons of Anarchy bunch, although they do their best). It's more like, "Open the book, here we are!"

Unfortunately one of them, Harker's daughter Edith, is ill-equipped for the life of a fearless vampire hunter. Edith Harker was simply born to find herself in jeopardy. Wolfman and Colan introduce her to the series that way in Tomb #7 (March 1973), and in "Screaming House" (as its friends call it; the rest of you must refer to it in full, with an honorific of your choice), she really finds herself in a mess, the likes of which no heart-felt talk with Sheriff Andy Taylor, Mrs. Garret or Mr. Belvedere can solve. After a lot of posturing on both sides and some ineffectual hand-to-hand, Dracula spirits Edith away to a shabby old house so he can toy with his adversaries rather than just kill them outright.

With his mastery of vertigo-inducing camera angles, Colan expertly depicts the abduction, which is quite alarming as Dracula transforms only partially into his bat-form. This emphasizes his otherworldly aspects by making him a grotesque hybrid creature, plus it gives him enough strength to carry Edith through the air. He needs those membranous arm-wings to do two things at once.

And the titular screaming house is foe unto itself. It's full of rotten floorboards that give way at inopportune times and Dracula's hidden away traps of his own, like the black widow cages he slips around the corner beneath Frank Drake's feet at one point. The good guys split up to cover more ground and render themselves even less effective against Dracula and it all comes to a tragic conclusion.

While the story itself is pretty straightforward, at least compared to later issues (which would feature adversaries such as a Communist Chinese brain in an aquarium, Dracula's hated vampire daughter, a faceless dead man and, later, his own weirdo son, an angelic/demonic pretty boy calling himself Janus) it has some important character development.

Once he plunges his cast into Dracula's fun house, Wolfman depicts Drake as scared almost out of his wits to the point of stuttering as he speaks. And yet the guy still pushes on alone. While Drake is in a state of transition from callow rich jerk to bumbling vampire avenger to intrepid daredevil hero, it helps reinforce the danger Dracula personifies. Remember, when you go against a vampire it's not just your life that's in hazard; it's your very soul. And with Dracula the series anti-hero, there's always the chance over-familiarity with the character and his motivations will weaken his menace and turn him into just another ineffective Marvel villain fond of soliloquys in the dark. This is especially true if the characters in the book come to view him as ho-hum.

Another important character point is the scarring of Rachel's face. Bats, released by Dracula, attack the group and Rachel gets a makeover. These scars become part of her character and eventually symbolize the hardening of her spirit. So important are these scars, when Wolfman and Colan resurrect Rachel years later in their Tomb of Dracula miniseries, it's through a kind of possession that involves a brand-new character tearing at her own face until she resembles Rachel and loses her own identity.

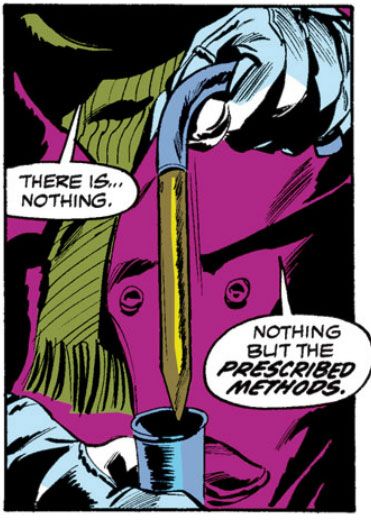

The final and most poignant element is Edith's fate and the matter-of-fact way Quincy deals with it. While Frank reacts with very human but misguided compassion and hopefulness, Quincy Harker knows from experience there is only one thing to do. Wolfman could easily cop out at this point and offer a last-minute reprieve in the form of some never-before-heard-of cure, but no. Instead, he sacrifices a character to the betterment of the story. It's a moment reminiscent of the scene from Stephen King's 1976 novel 'Salem's Lot where protagonist Ben Mears is forced to drive a stake through Susan Norton's (his vampirized girlfriend) heart. King changes viewpoint characters throughout his story, spending a great deal of time and care making readers empathize with Susan by allowing them to see events from her perspective. Her loss in the narrative gains impact because we think of her loss as tragic unto itself rather than merely something that incites Ben's actions towards the climax.

Wolfman hasn't had enough time to do as much for Edith. Because her fictional career ends so abruptly, she remains something of a punching bag of a character. And yet, Harker's coldly pragmatic method of dealing with her is chilling. This is what separates a true horror story from an adventure that uses horror trappings. Horror forces characters into painful choices, the loss of sanity, of limbs, of life, of loved ones.

No comments:

Post a Comment